On the night of September 1, 2023, a Saudi Pro League soccer game was broadcast directly into Iranian homes. Less than a year ago, such a broadcast would have been unthinkable. Iran and Saudi Arabia were sworn adversaries whose football teams could not even play each other except on neutral turf.

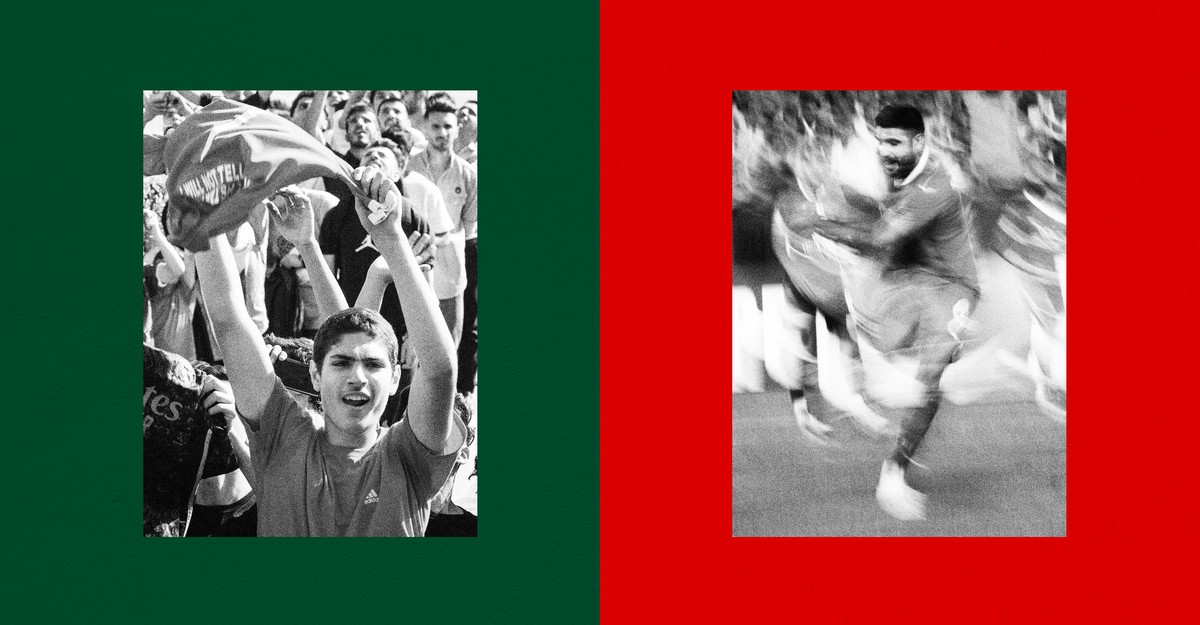

The broadcast didn’t disappoint. Nor was it expected to, as the league, with abundant coffers, now features an ever-expanding roster of players who are among the most celebrated to have ever played the game. When one of those players, the striker Karim Benzema, scored a world-class, side-heel clip of a goal, the Iranian sportscaster, in awe of what he and everyone else had just witnessed, lingered on the player’s full name with near-veneration: Karim Mostafa Benzema.

The match ended with seven goals exchanged, at least one of which, by the Serbian player Aleksandar Mitrović, was almost the equal of Benzema’s. And the game itself was an instant classic, the perfect example of why soccer is called “the beautiful game.”

Afterward, on Iranian social media, spectators rhapsodized about what they had just witnessed on state television. “Dear God, I ended up watching this game instead of the Rome vs Milan match,” a fan named Ali wrote. From the Gulf port city of Bushehr, home to the Middle East’s first civilian atomic reactor, someone else wrote: “One of the best clasicos I’ve ever watched in my whole life.”

A soccer match had to promise to be that good for Iranian fans to forgo a simultaneous broadcast of a top Italian professional-league game in its favor. Even more remarkable was the fact that the match was from neither Spain’s LaLiga nor the British Premier League, but rather, between two of Saudi Arabia’s top three teams:

“I never would have believed Saudi football could be so gorgeous.”

“Way to go Arabs!”

“Who would have thought one day we’d sit and watch the Saudi league?”

“Before long we’ll be asking one another if you’re an Al-Ittihad fan, an Al-Hilal fan or an Al-Nassr fan. So long, Europe!”

The decision to air Saudi league soccer on Iranian television, and to invest Iranian fans in its outcome, was not an idle one on the part of the Islamic Republic. Rather, it reflects a changing orientation in Tehran—one that few saw coming in 2016. That year, the ever-deteriorating relationship between the two heavy hitters in the Middle East took an especially sharp turn for the worse, when Saudi Arabia executed several dozen of its Shiite citizens, and demonstrators burned the Saudi embassy in Tehran. The two countries severed all diplomatic ties. Tensions spilled over into open violence in the years that followed, with Tehran and Riyadh engaged in proxy contests in Yemen, Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria.

But Iran has a way of periodically dropping a bombshell on the rest of the world. The Saudi-Iranian rapprochement that China brokered in March 2023 was one such bombshell. And now Tehran is quietly following through with a dedicated rehabilitation of Saudi Arabia in numerous aspects of Iranian public life.

Take television: A popular Iranian spy series called Safe House first aired in 2020 and included an episode in which an agent of the Islamic Republic interviews a captured enemy spy, and one where he gleans valuable information from a source in Baghdad. The focus in both scenes is a certain Saudi notable who, in real life and over a very long, very distinguished, and very anti-Iranian career has occupied powerful positions in intelligence and diplomacy. After the rapprochement, the series was edited and reissued, with the focus on the nonfictional dark eminence deleted. Now neither the Saudi notable nor his supposed inimical machinations exist in the universe of the show. Notably, government-backed media outlets such as KhabarOnline and Etemad ran reports on the series’ sudden turnabout.

At the same time, ultraconservative government newspapers such as Kayhan and Vatan-e ٍEmrooz, which were until a year ago die-hard foes of the Saudis, have completely changed their tune. A promised exchange of ambassadors has already taken place, and in a recent visit to Riyadh, after nearly a decade’s hiatus in visits, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian went so far as to emphasize Iran’s support of the Saudi bid to host a world’s fair in 2030. For its part, Arab News, the most important English-language Saudi paper, dedicated its front page to celebrating the Persian New Year in March. The seven Arab states that edge the Gulf (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Iraq) prepared for a comprehensive sit-down with their Persian neighbor on September 23 in New York. That meeting fell through because of scheduling conflicts and a continuing maritime-border dispute between Iraq and Kuwait, but lower-level talks are rumored to be scheduled for the near future.

The immediate dividend for Iran is desperately needed hard currency. The rift between the two countries had cost Iran: Before 2016, Shiite Arab pilgrims from Saudi Arabia and Bahrain were a solid source of tourism in the Iranian holy city of Mashhad, such that, according to Mohammad Ghanei, the chair of the city’s hotelier association, merchants from these countries booked up to 10 four- and five-star hotels in the city year-round. The termination of diplomatic relations between Iran and Saudi meant that few, if any, Gulf Arab tourists, and certainly none from Saudi Arabia, would be traveling for pilgrimage or to visit Iran’s northern Caspian Sea region, another favorite destination.

The dialogue that broke out between these two adversaries in 2023 was a remarkable thing. Perhaps the parties were simply exhausted, like soccer players who had run around a pitch for 90 minutes and fought to a draw, only to have to play an extra 30 minutes and ultimately go for penalty kicks. Or maybe priorities changed. The United States had pulled out of Afghanistan and begun a not-so-delicate retreat from the Middle East; war had come to Ukraine; and the U.S. and China seemed ever less inclined to pretend that their brawl for global supremacy was just about economics.

Change had come, in other words; yet Iran and Saudi Arabia found themselves facing the same Gulf, alone, and with the same neighbors or near neighbors. Neither was going anywhere. In an interview in The Atlantic a year before the Iran-Saudi agreement, Mohammed bin Salman had this to say: “Where is the potential in the world today? It’s in Saudi Arabia. And if you want to miss it, I believe other people in the East are going to be super happy.”

The Islamic Republic of Iran, for one, is super happy. So are Iranian soccer fans, who anticipate regularly seeing some of the legends of the game—Benzema, Cristiano Ronaldo, Neymar, Sadio Mané, and likely eventually Mohamed Salah—come play on Iranian soil during Asia’s AFC Champions League matches. Such is the gift that Saudi Arabia has brought to Iranian fans, a sizable number of whom booed their own national team during the fall 2022 World Cup, after Mahsa Amini’s death touched off a wave of domestic protests. Both Iran and Arabia are civilizations of long standing that have seen their share of human inconstancy—enough, perhaps, to be inured to the fluidity of history, let alone of geopolitical alignments. On the streets of Iranian cities, you’ll still find pictures of Iranian “martyrs” of the Bosnian War. Yet, three decades later, fans eagerly await the arrival of a Serbian national, Mitrović, who happens to play for a club from the heart of the Islamic world, Saudi Arabia.

During the Women’s World Cup in Australia this summer, the head of Iran’s soccer federation and his Saudi counterpart met and agreed that at last the two countries’ teams could play on each other’s territory. Iran and Saudi Arabia, alongside South Korea, Japan, and Australia, are traditional powerhouses of Asian soccer; the two countries’ teams will inevitably meet again and again. Now they’ll do so on home turf, and their fans will see each other inside their home stadiums and on TV—they will see each other being human, and just as smitten with football as their rivals across a body of water whose very name remains in dispute between Arabs and Persians.

Just last week, the Saudi team, Al-Ittihad, withdrew from a match in the Iranian city of Isfahan, reportedly in protest of having to pass by a statue of the slain Quds Force leader Haj Qasem Soleimani on the way to the pitch. Iran’s foreign minister spoke with his Saudi counterpart, and the match will likely be rescheduled—a testament to just how far the two countries are willing to go to make things work.

Soccer diplomacy has moved from the living rooms of Iranians into stores and malls. In the sports shops of the Moniriyeh district of Tehran, a perennial hot item is a kids’ Ronaldo jersey, which starts at $4, depending on the quality, and is completely bootleg, like nearly all sports clothing sold in the city. The Portuguese superstar’s colors are not the white of his storied former club Real Madrid, nor the red of another giant, Manchester United, but rather the yellow and blue of Al-Nassr Football Club, from Riyadh. Al-Nassr and Ronaldo played their first game on Iranian soil on September 19 against another of Asia’s most decorated teams: the Iranian team Persepolis, whose name translates to “the city of Persians.”

So long, Europe.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2023/10/saudi-arabia-iran-soccer-diplomacy/675558/

.